DALLAS — Long before engineers spun 3D models of airplanes on screens, they built them the old-fashioned way, with pencils, rulers, and plenty of patience. Every curve was drawn by hand, every calculation worked out on paper, yet somehow those rough sketches became the flying machines that changed how we move around the world.

It’s hard to believe that icons like the Concorde and the Boeing 747, the “Queen of the Skies,” were created without CAD software. Thousands of hand-drawn blueprints, slide rules, and early computers helped turn those ideas into reality.

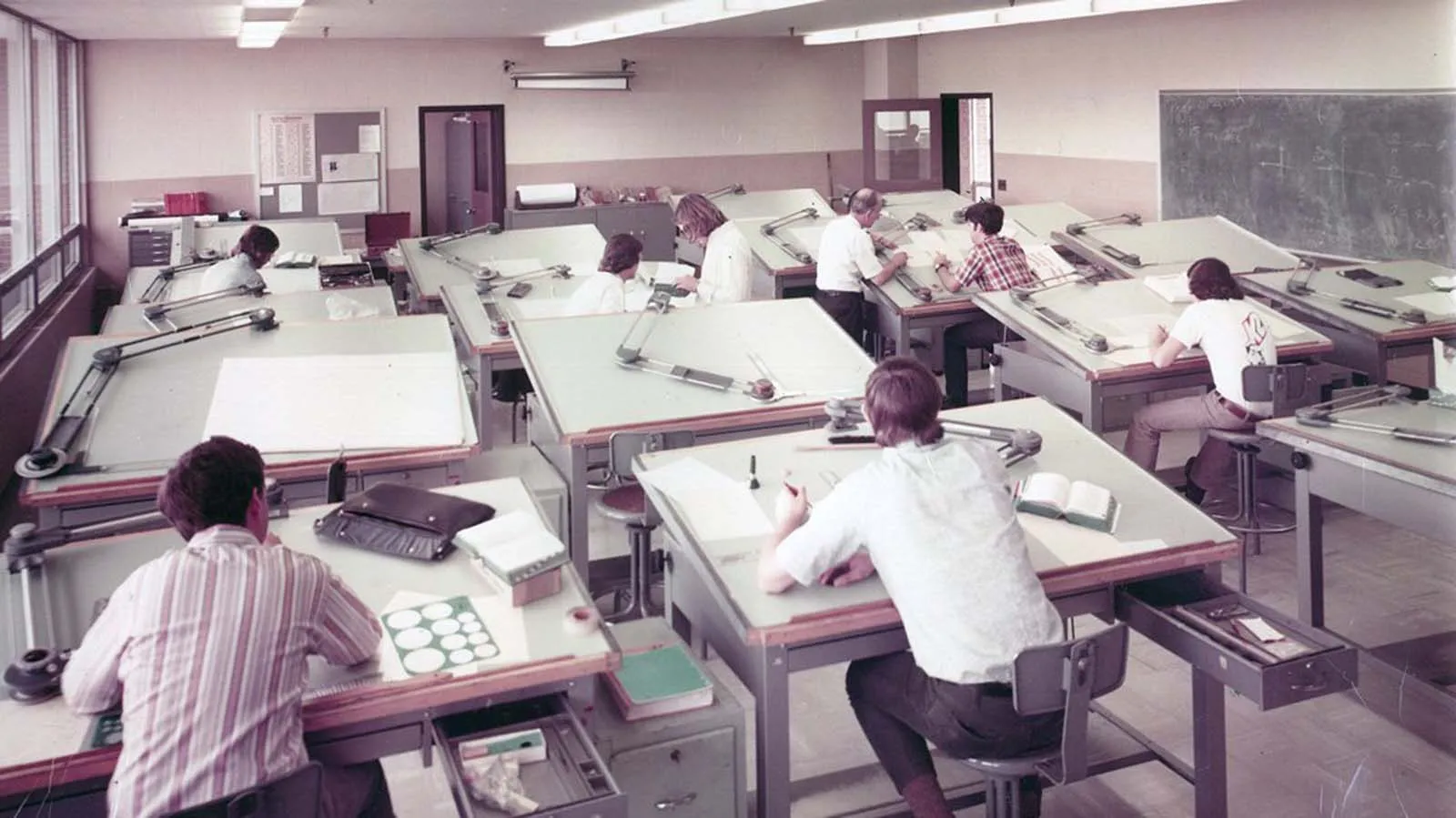

The Age of Drafting Tables

Before computers entered the picture, every airplane began life on a drafting table, a large, tilted wooden desk built for precision. Engineers could adjust it to sit or stand, and often spent entire days leaning over rolls of tracing paper. Their desks were cluttered with compasses, French curves, and slide rules. The quiet scratch of pencils filled the room. It was slow work, but deeply personal and full of craft.

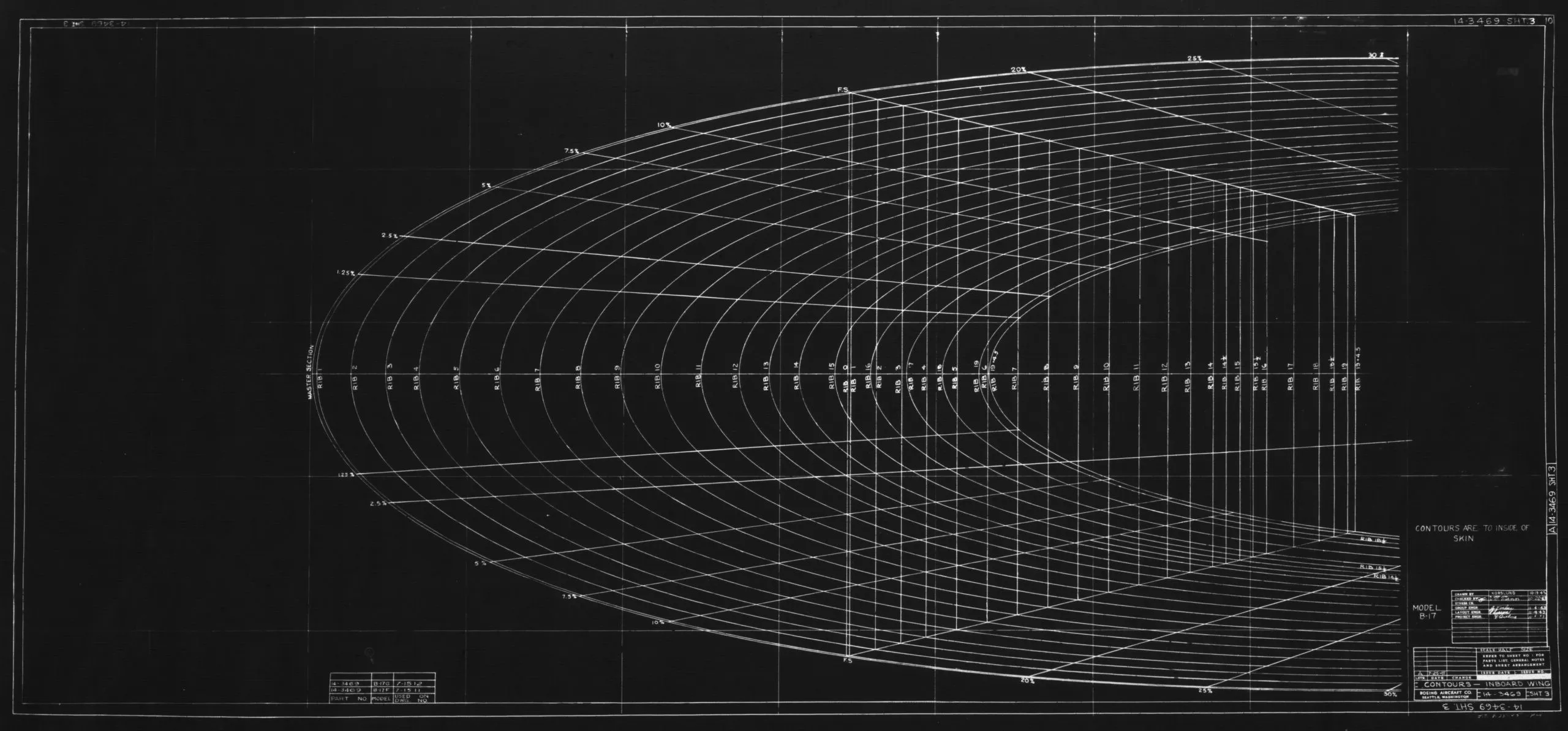

Drawing Curves with Splines

Aircraft shapes are defined by smooth, flowing curves so air can move cleanly across the surface. To draw these by hand, engineers used a flexible strip called a spline, held in place by small metal weights nicknamed “ducks.” Once bent into the correct curve, the line was traced to create an aerodynamic contour. That same word, spline, is still used today in 3D design software like CATIA and SolidWorks, only now it’s digital.

When Computers First Arrived

By the late 1950s, huge computers started appearing in engineering offices. They weren’t sleek laptops; they filled entire rooms, ran on punch cards, and mainly crunched numbers. These early machines could calculate lift, drag, and stress loads, but the drawings still happened by hand. The math became faster, but the design remained an art form.

The First Digital Experiments

In the 1960s, a few bold engineers wondered: Could a computer actually draw? That question led to Sketchpad, created in 1963 at MIT by Ivan Sutherland, the first system that let users draw directly on a screen with a light pen.

Soon after, Boeing, Lockheed, and McDonnell Douglas began experimenting with digital drafting. Those systems were primitive, black-and-white, slow, and limited, but revolutionary for their time. Even then, jets like the 747 and Concorde were still drafted mostly by hand.

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, computers became smaller and more powerful. A significant turning point came from France: CATIA, short for Computer-Aided Three-Dimensional Interactive Application, was developed in 1977 by Dassault Systèmes for fighter jet design. For the first time, engineers could model an entire airplane in 3D, test how parts fit together, and adjust designs instantly. What once required thousands of sheets of paper could now fit on one screen. Airbus, Boeing, and Lockheed soon followed.

The Airbus A320, launched in 1987, was among the first airliners designed primarily on 3D CAD, marking the true beginning of the digital design age.

The Boeing 777 became the world’s first entirely digitally designed airliner in the early 1990s. Boeing ditched paper blueprints entirely; every part, from bolts to cables, was modeled in CATIA. Teams across the world could now collaborate virtually.

The result was a success story: the 777 became one of the most dependable aircraft ever built, the first truly “paperless” jet.

Why Modern Aircraft Take So Long to Build

You’d think advanced computers, AI simulations, and virtual wind tunnels would make aircraft design faster. Oddly, it’s slower now. Take the Boeing 777X. Its first flight was in 2020, but its entry into service has been pushed to 2027. That’s seven years between first flight and delivery, something that would’ve sounded impossible in the 1960s when the 747 went from idea to flight in just four years.

Today’s airplanes are far more complex. Certification is tougher, safety standards are stricter, and designs are pushing limits. The 777X’s folding wingtips, for instance, are a first for a commercial jet, and that means new tests and approvals.

Every mechanical system, including engines, avionics, and flight controls, must be checked through endless simulations and real-world testing. And since everything is digitally linked, even a minor tweak can trigger months of re-verification. Computers make design more precise, but they also open doors to innovations that need extra proof they’re safe.

When Software Glitches Hit Hard

Back in the mid-2000s, when Airbus was getting ready to bring the A380 into service, something strange happened: engineers found that miles of wiring inside the plane were just too short. At first, it sounded like a minor issue, but it turned out to be a huge one. After some digging, Airbus realized what went wrong. Different teams across Europe were using various versions of the same software. The German and Spanish engineers were still working with CATIA V4, while the French and British teams had already switched to CATIA V5. The two versions didn’t work well together, so when all the parts came together in Toulouse, the wiring simply didn’t fit.

It might sound like a simple software problem, but it caused a massive delay. Airbus had to redo thousands of wiring harnesses, which pushed the A380’s launch back by nearly two years and cost the company around US$US6 billion. The whole project ended up costing roughly US$25 billion, and Airbus said it lost about €2.8 billion in earnings.

A tiny mismatch in software ended up being one of the most expensive mistakes in aviation history, proof that even a small digital gap can cause a giant to stumble.

From Hands to Hardware: The Lasting Legacy

The story of aircraft design is really a story of people adapting to their tools. For most of the 20th century, airplanes were drawn by hand, line by line, by engineers who turned imagination into reality. Computers replaced pencils and tracing paper, but not the mindset. The patience, precision, and care of those early draftsmen still guide today’s designers, even as they work in pixels instead of graphite.

Modern airliners, built entirely in 3D and tested virtually before a single part is cut, still carry the spirit of that earlier era. The shift from graphite to graphics wasn’t a replacement; it was an evolution. Every time a jet lifts off, it quietly honors those who once drew the sky by hand, one careful line at a time.