ATLANTA — Commercial aviation became an essential, if often overlooked, instrument of the U.S. civil rights movement, carrying Martin Luther King Jr. across a divided nation and beyond during the jet age.

From packed Southern schedules to early international jet routes, airlines enabled King’s relentless travel while exposing the contradictions of a country that promoted modern mobility but enforced segregation on the ground. His journeys unfolded at the intersection of operational aviation realities, racial injustice, and rising security threats, long before air travel became routine for most Americans.

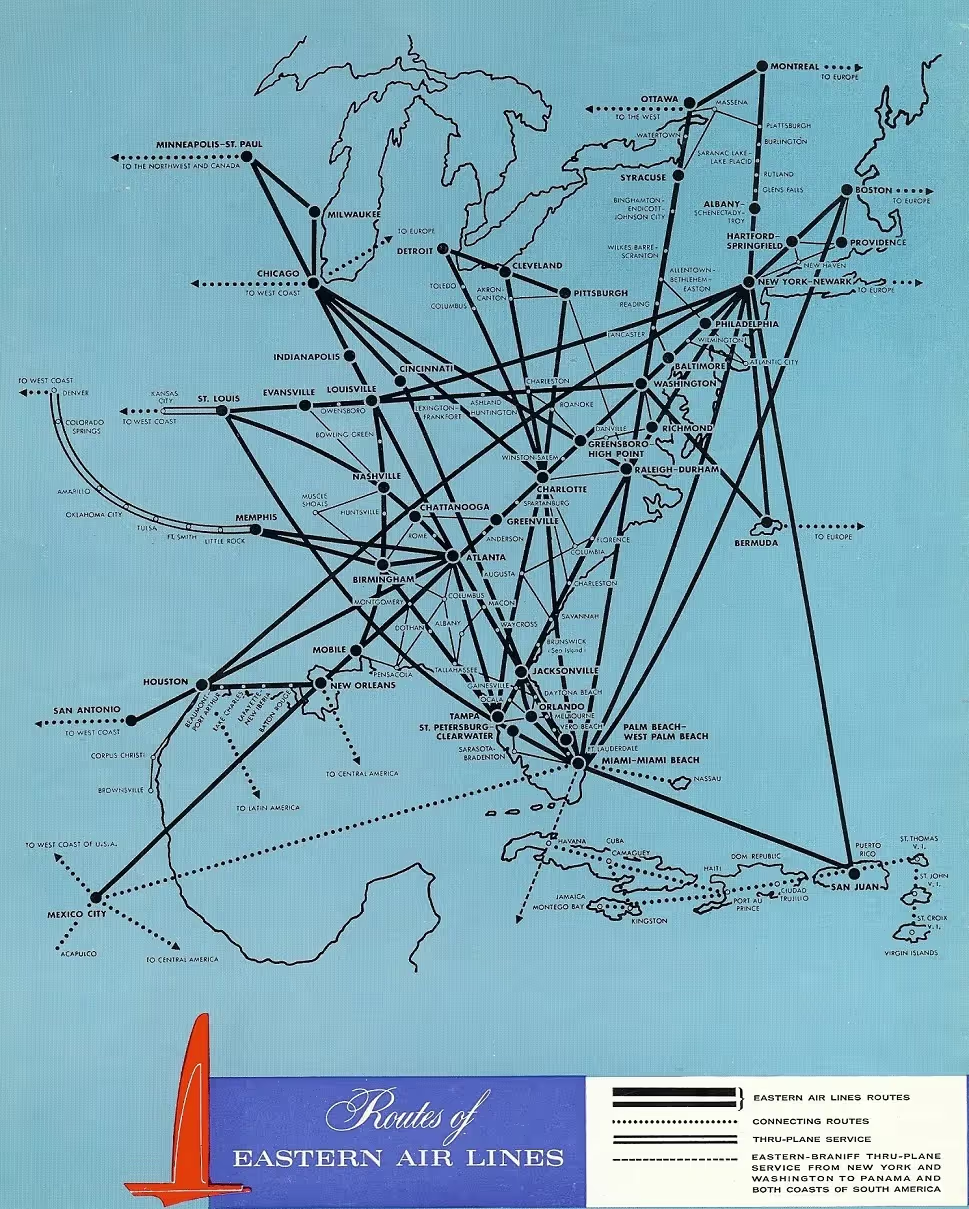

Eastern Air Lines and the Geography of the Movement

For most of the 1950s and 1960s, Eastern Air Lines functioned as Martin Luther King Jr.’s primary carrier. The choice reflected geography rather than preference. Eastern dominated the U.S. Southeast, operating dense schedules linking Atlanta with Birmingham, Montgomery, Memphis, Miami, and New Orleans—cities that formed the backbone of the civil rights struggle.

Based in Atlanta, King relied on Eastern’s high-frequency short- and medium-haul routes to maintain a punishing travel pace that blended sermons, organizing meetings, court appearances, and fundraising engagements. The airline’s network effectively compressed distance at a time when driving across the Jim Crow South posed both logistical and physical risks.

Aircraft of the Era: From Propellers to Jets

King’s early flights likely occurred aboard piston-engine aircraft such as the Douglas DC-6 and Lockheed Constellation, still common on Southern routes in the early 1950s. As Eastern transitioned into the jet age, King’s travels increasingly aligned with newer equipment, including the Boeing 727 and, later, the Douglas DC-9.

The DC-9 proved particularly well suited to Eastern’s regional operations. Short runways, quick turnarounds, and frequent departures made it ideal for connecting mid-sized Southern cities—exactly the markets King visited most often. While no passenger manifest definitively identifies a specific aircraft type, fleet composition and route economics strongly suggest DC-9 operations dominated his final years of travel.

April 3, 1968: The Final Flight

King’s last journey underscores the risks that shadowed his movements. On April 3, 1968, he boarded Eastern Air Lines Flight 381 from Atlanta to Memphis. The flight—widely believed to have been operated by a DC-9-31—departed after delays caused by a bomb threat, a grim but familiar reality by that stage of King’s public life.

Accompanied by civil rights leaders including Andrew Young, King arrived in Memphis hours before delivering his final speech at the Mason Temple. The following day, he was assassinated.

Memphis International Airport later commemorated Flight 381, recognizing its place in both aviation and American history.

Security, Surveillance, and the Risks of Visibility

By the mid-1960s, King traveled under constant threat. Bomb warnings, hostile crowds, and FBI surveillance became routine. Commercial aviation magnified both his reach and his exposure: public schedules, recognizable aircraft, and predictable routes created vulnerabilities that modern security protocols had not yet evolved to address.

Despite these risks, flying remained the fastest and safest option available, especially as King’s international profile grew.

International Routes: India and Beyond

King’s 1959 journey to India, undertaken to study Mahatma Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolent resistance, likely involved transatlantic jet travel aboard Pan American World Airways or Trans World Airlines, the only U.S. carriers operating intercontinental routes at the time. Aircraft such as the Boeing 707 or Douglas DC-8 would have represented the cutting edge of global aviation.

While no surviving ticket records confirm the exact routing, the operational reality of the era leaves little ambiguity regarding the carriers involved.

Segregation at 35,000 Feet, and on the Ground

Interstate aviation fell under federal jurisdiction, meaning racial segregation aboard aircraft had already been outlawed. Airports, however, remained segregated well into the 1960s. King and his colleagues often moved freely through the cabin only to confront “white” and “colored” facilities inside terminals.

This contradiction of modern aircraft crossing state lines while discriminatory practices persisted on the ground made aviation a quiet but powerful symbol of the civil rights struggle itself.

After the Assassination: A Final Journey Home

Following King’s death, American Airlines transported his body from Memphis to Atlanta aboard a Boeing 727, carrying him home for burial. Though distinct from his lifetime travels, the flight marked aviation’s final role in his story, closing a chapter defined by urgency and sacrifice.

Legacy in the Jet Age

Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy is inseparable from the era that carried him. Commercial aviation allowed him to transcend geography, linking Southern churches to national audiences and connecting American civil rights to global conversations about justice and freedom.

In an age before hub-and-spoke networks, mobile devices, or body scanners, airlines became silent partners in a movement that reshaped the nation. Every boarding pass, every departure gate, and every jet climbing out of Atlanta carried an exemplar of a better society.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)